- The rules governing the operation of the TPRM are set out in Annex 3 to the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organisation.

- Formally, the TPRB is the WTO’s General Council meeting “as the TPRB”. The General Council is the WTO’s highest decision-making body outside the Ministerial Conference.

- Thus, Section B of Annex establishing the TPRM states: “Members recognize the inherent value of domestic transparency of government decision-making on trade policy matters for both Members' economies and the multilateral trading system, and agree to encourage and promote greater transparency within their own systems, acknowledging that the implementation of domestic transparency must be on a voluntary basis and take account of each Member's legal and political systems.” (emphasis added).

- This can be seen in policies such as high tariffs, especially in the US and the Corn Laws in the UK (1815-46).

UK Trade Policy: An Independent Review

November 2025

Authors

Achyuth Anil, Thomas Baily, Amar Breckenridge, Michael Gasiorek, Charlotte Humma, Sahana Suraj, Fiona Smith

Contributory authors

James Black, Mattia Di Ubaldo, Alexander Fitzpatrick. Lindsey Garner-Knapp, Nicolò Tamberi, Valeria Terrones, Manuel Tong Koecklin, Maurizio Zanardi, Dongzhe Zhang

Download the UK Trade Policy: An Independent Review

Click on the contents bar above to navigate the report or download a pdf version.

Executive summary

Making good trade policy is difficult, and in today’s world, considerably more difficult than even a few years ago. This review provides an independent, evidence-based assessment of UK trade policy in 2025, in a world where the UK is grappling with:

- Structural economic challenges at home.

- Rising protectionism, often linked to economic security and intensifying geopolitical competition abroad.

- Rapid technological change.

- An expanding set of policy objectives, climate change, biodiversity and inclusiveness, that trade policy is expected to support.

This review evaluates how current UK trade policies respond to these pressures, how effectively they serve the UK’s economic and interests and broader public policy goals. It identifies where changes may be needed to ensure consistency, coherence, resilience, and long-term prosperity.

The review does this by examining how trade policies can contribute to productivity and economic growth while also addressing a broad set of concerns and commitments around economic security, sustainability, digital transformation, and social inclusion. It identifies cross-cutting challenges, some of the key trade-offs that exist between various aspects of government policy, suggests areas where policy coherence is lacking, and proposes actionable policy recommendations. The review draws on government data, expert consultations, and public engagement — including a public call for evidence, roundtables and a Citizens’ Jury.

This review coincides with, and is intended to complement, the World Trade Organisation’s recently published and excellent report on the UK under its Trade Policy Review Mechanism (TPRM). The TPRM process focuses on documenting the trade and related policies undertaken by countries. It is less directed at addressing the question “why”, identifying priorities, or evaluating how trade policies interact with other policy objectives. But the ‘why’ question does need to be asked, which in turn leads to consideration of priorities and broader policy interactions.

That is because the world of trade policy today is very different to the world in 2016, when the UK voted to leave the European Union, let alone the one in which the WTO was created. While many still support open trade, others, including some of its staunchest supporters in the past, are challenging the concept and the multilateral rules that have underpinned trade. In addition, there are other priorities, such as economic security, supply chain resilience, climate change, sustainability, and inclusiveness, which have become more important than before. In this context, it is important to know what is being prioritised, why and how. This is especially relevant to the UK.

With this backdrop in mind, this review:

- Maps out the key characteristics of the UK economy and what the UK trades.

- Identifies UK trade policy priorities.

- Analyses how trade policy decisions are made—including the role of devolved governments, advisory bodies, and Parliament.

- Evaluates the UK's international engagement, including WTO participation and free trade agreements.

- Assesses trade policy through four critical themes: economic security, trade and the digital transformation, sustainability, and inclusiveness.

- Provides a transparent and systematic methodology that can be replicated in future reviews or applied to different policy topics.

This Executive Summary provides a summary of key messages framed around the pressures and challenges identified above. In so doing, we draw upon all the chapters of the report.

UK trade policy is at a challenging juncture

This review of UK trade policy takes place against a backdrop of persistently weak UK productivity growth. Even before the pandemic, UK productivity growth had slowed significantly; since the pandemic, it has trended below the OECD average. Weak productivity constrains income growth, competitiveness, and the capacity of the UK economy to generate improvements in living standards. Boosting productivity and economic growth remains the UK Government’s central strategic objective.

Trade policy can help with this: there is a long-established empirical relationship between trade, productivity and growth; and firms that trade tend to be more productive. Exposure to global markets encourages innovation, allows firms to specialise, and improves access to inputs, technologies, and global supply chains. The review highlights that the UK is relatively open to trade, with a trade-to-GDP ratio of around 65%. More than 6.5 million jobs depend on exports, of which 1.5 million are in manufacturing and 5 million in services. Services trade in 2024 accounted for 57% of UK exports and 35% of UK imports. Yet only a small share of firms are engaged in international trade - 11.5% of firms export, 12% import and only 6.5% of firms do both and most trading firms are small - roughly 95% of UK exporters or importers have fewer than 50 employees. It is the smaller firms that are precisely the ones that find the barriers to trade hardest to overcome.

However, the ability of trade policy to support economic growth is constrained by several factors, starting with significantly higher trade costs between the UK and its two most important partners, the EU and the US. The reflects, respectively, the UK’s decision to leave the EU Single Market and Customs Union, and the US’ unilateral shift to a protectionist policy stance.

The latter development is symptomatic of a broader trend that poses a significant challenge to trade and to middle-size economies like the UK: the undermining of global trade rules, and the use of trade policy as an instrument of geopolitical rivalry. While the UK has pursued an active trade negotiation agenda, concluding a number of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) that collectively cover 70% of UK imports and 61% of UK exports of goods and services, these may struggle to mitigate the increase in trade costs with major partners, and more broadly, a wider shift towards fragmentation in global trade.

Understanding UK trade in a fragmenting world

The governance of global trade is shifting from a system based on predictable and enforceable rules and principles of non-discrimination to one based on more selective and discretionary arrangements. Under such arrangements, access to markets may be conditioned by other factors, notably security or supply chain considerations. This has been evident in the US’ unilateral embrace of protectionism and recent imposition of tariffs across its trade partners, but is also visible in some of the UK’s other major trade partners.

The challenge for the UK is that it is dealing with this change from a position that was already made more fragile by the effects of leaving the EU. Evidence suggests that leaving the EU has been associated with falls in goods trade by up to 30% and services exports, in affected sectors, by around 16%. The EU remains the UK’s single largest trade partner, accounting for 41% of UK exports and 52% of imports, so further reducing trade costs with the EU is important for the UK. Recent “reset” negotiations between the UK and the EU may hold promise for some sectors, such as agrifood and energy. But they have yet to address the main aspects of UK trade, such as regulatory barriers or services, which, as already observed, dominate its economic structure.

Global fragmentation is also an issue for the UK because its trade is significantly more dependent on international linkages than is the case for the EU, the US and China – the UK’s three largest trade partners. Around 28% of the value of UK-manufactured exports is accounted for by linkages to foreign sources. Data for exporting firms shows that the ratio of their services imports to goods exports has risen substantially in recent years, illustrating both cross-national dependencies, and dependencies between goods and services trade.

These linkages highlight the issues that can arise when partners follow a more selective and restrictive approach to trade, and condition market access on other factors. Consider the US-UK Economic Prosperity Deal (EPD) signed in 2025. While this provides some shelter from US tariffs, it also leaves applied rates of at least 10% on UK exports, relative to an average of less than 3% which the UK has previously faced. Moreover, the EPD specifies that access to US markets is conditional on the UK adjusting to US perceptions of security by reducing linkages with partners (read China) that the US may deem hostile to its national security. The rise of China’s share in UK imports of goods from less than 3% in 2000, to 11% in 2024, is one of the main observable changes over the last decade. Furthermore, 50% of UK imports from China can be described as “high dependency” i.e., products for which China accounts for more than half of the UK’s imports by value. China is also very active in the Asia-Pacific region, which the UK has targeted as a priority in its trade expansion.

Positioning UK trade policy - domestic dimensions and the scope of policy activism

Domestically, until the publication of the Trade Strategy in 2025, there has been a lack of strategic direction for UK trade policy. The Trade Strategy is an important step, but without clear institutional structures and processes for trade policymaking, it risks continuing the piecemeal approach that has characterised trade policy in the UK for almost a decade.

The institutional basis for trade policy has evolved incrementally, through a combination of statutory (legislation) and non-statutory processes. A key piece of existing legislation is the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act (CRAG), passed in 2010, which requires all international treaties to be laid before Parliament. The principal statutory bodies are the Trade Remedies Authority and the Trade and Agriculture Committee, both established in 2021. Formally, the Devolved Administrations have no constitutional role in the development of UK free trade agreements, but they are included in the UK Government’s trade policy processes and implementation efforts. Without a constitutional basis, inclusion remains based on goodwill rather than legal precedent.

In practice, UK trade policymaking is supported by a range of advisory groups, the name, composition and purpose of which have changed considerably over recent years. In addition, many elements of trade policymaking - public consultations, parliamentary updates, and negotiation strategies - remain discretionary. Consequently, significant elements of transparency, accountability and stakeholder engagement in the UK's trade policy process remain non-binding and subject to change. The balance of opinion from parliamentarians, external stakeholders and experts is that there is insufficient scrutiny of trade agreements and that consultation processes are overly ad hoc and lack transparency. Relatedly, there is limited regular reporting on the barriers to trade and investment faced by UK firms, and on the ex-post assessment of the effectiveness of trade policy measures and trade agreements.

The Modern Industrial Strategy and the Trade Strategy, both published in 2025, are key documents that set out the broad direction of travel. They build on strategies and policy orientations developed, in an incremental and piecemeal manner, by previous governments. Our analysis reveals a certain continuity in policy thinking across governments – though priorities have shifted. Growth has been the dominant theme, with certain other key themes considered important, but secondary. These include: economic security; sustainability (which includes the UK’s legally binding commitment to net zero); harnessing the digital transformation; and addressing matters of social inclusion. It is worth noting that in contrast to policy pronouncements, public preferences expressed in our Citizens’ Jury, held in the preparation of this report, and the Government’s Public Attitudes to Trade Tracker, suggest that the public appears to prioritise these other goals as much as the goal of economic growth.

The Industrial Strategy prioritises eight sectors, and identifies interventions that are primarily domestic in nature, but many of which also have trade spillovers. Chief among these are interventions that use public funds, through subsidisation. The Subsidy Control Act of 2022 was specifically intended to provide greater flexibility in subsidisation. By and large, interventions in various sectors have been based on identifying sources of market failure, usually in research and development, the scaling of activities, and barriers to commercialisation. The logic is also that such interventions will not only address productivity and growth objectives; they will also ensure progress against the other policy themes. For example, correcting market failures affecting digital technologies such as AI and Quantum computing, or the production of advanced semiconductors, can stimulate productivity and growth, while also furthering economic security and digital transformation objectives.

To the extent subsidies target market failures at source, such approaches are economically defensible, and, as mechanisms to achieve policy outcomes, are preferable to trade restrictive measures. However, more attention needs to be paid to the trade-offs that may exist between various policy objectives and thus the priorities. Consider sustainability, for example. The dominant line of policy thinking is that stimulating domestic “green” industries can enhance both industrial activity and environmental outcomes. However, our analysis of government discourse on the matter shows this line of thinking also neglects the trade-offs that may exist, for example, between enhancing the domestic growth of these industries, versus the efficiencies that may come from imports and specialisation. Moreover, existing evaluation frameworks for interventions using public funds by and large do not provide for an explicit treatment of trade spillovers, and the efficiency costs they may create.

Other aspects of Industrial Strategy that have important trade policy spillovers include regulation. Perhaps the most significant area is in relation to digital activities, given the role of services in UK trade, and the fact that 70% of services are digitally delivered. Here, the approach followed by the UK Government may be characterised as a “pragmatic one”, in the sense that it has tried to steer a middle course between the more laissez-faire approach of the United States, and the more prescriptive approaches followed by the EU. This is perhaps most readily seen in the UK’s approach to digital markets and to AI regulation. The question for the UK is how far this can be sustained as it seeks deeper integration with various partners. The EPD, for example, envisions negotiating ambitious provisions on digital trade, which may require greater alignment with US approaches. The subject of digital regulation has, in any event, been a sensitive issue for the US in trade negotiations.

International positioning – pragmatism versus principle

The importance of multilateral institutions to the UK is underscored by its active engagement in WTO processes. This includes initiatives on possible reforms to the multilateral trading system, sponsoring or leadership of various plurilateral negotiations, including those under the so-called Joint Statement Initiatives, notably on e-commerce and on services regulation. The UK has also been an active proponent of the WTO’s work programme on trade and gender, though arguably there also remains a substantial domestic agenda here for the UK to tackle.

The UK also remains an important proponent of the WTO’s development dimension, both through its Developing Country Trading Scheme (DCTS) implemented in 2023 and the Economic Partnership Agreements with developing countries. The DCTS increases the number of tariff lines eligible for preferential treatment from 80% to around 90%, and simplifies rules of origin.

The UK’s overall trade policy settings remain liberal. The introduction of the UK’s Global Tariff simplified UK tariffs, increasing the share of imports coming in duty-free, on non-preferential terms, to around 70%, relative to 52% under the EU MFN tariff, with the weighted average MFN tariff falling from 2.1% to 1.5%. The UK is also significantly more liberal in services, notably digital services, than partners in the OECD and the EEA. Data from the OECD point to liberalising steps by the UK since 2020, specifically in the area of the movement of people, which is notable given political sensitivities around this topic. The Trade Strategy, commendably, highlighted the importance of imports to the UK economy.

More restrictive elements of policy may be found in relation to trade remedies. In this area, the UK has implemented changes that provide more ministerial discretion on whether to implement remedies. It is also considering further changes to its approach to “trade defence” more broadly, and widening ministerial discretion, though it is not clear what this may entail. The main reason invoked for these steps appears to be economic security.

Indeed, a significant aspect of the Trade Strategy was that it highlighted the rise of economic security as a paradigm for considering the UK’s positioning internationally. As observed above, this mirrors developments overseas. The UK does not have a formal definition or policy framework for economic security. But parsing the Trade Strategy and documents produced by successive governments suggests that economic security encompasses notions of resilience to shocks and to coercive actions by other states, and national security.

FTAs offer one potential mechanism for integrating economic security with more conventional policy aims relating to commercial opportunities and growth. Indeed, many of the UK’s FTAs contain language – even if aspirational – relating to resilience and security. A challenge to the UK, however, is that its approach to FTAs has operated on a “WTO-plus” basis i.e. agreements that seek to go beyond the WTO baseline. They also reflect a concept of “open regionalism”: FTAs allow coalitions of partners to integrate and offer others the possibility to join (as is the case with the CPTPP). The main challenge is that this “open, WTO-plus” approach is running into the more closed, “WTO-minus” approach of certain other partners, principally the US. The EPD is an example of such a closed, WTO-minus agreement.

The UK’s position is that it will be pragmatic in the sense that it is open to striking arrangements of an unconventional – and if necessary, WTO-inconsistent – nature, if it is in its interests to do so, as with the EPD. In addition, the UK has signed over 60 “mini deals” i.e., trade agreements that are, strictly speaking, outside of WTO rules though not necessarily in contravention of them. While this might be considered pragmatic, it does not obviate the basic tension between WTO-plus and WTO-minus approaches. Nor does it address the fact that many of the broader issues of interest to the UK – especially security and sustainability – are collective action issues which ultimately require multilateral rules and institutions. Public attitudes in the UK are broadly supportive of multilateral institutions.

Conclusion

The review highlights the multiple demands placed on trade policy, reflecting both domestic requirements and a challenging, evolving international environment. Both of these forces require choosing the right mix of policy instruments and assessing trade-offs correctly. On the domestic front, the approach to tackling market failures that inhibit productivity and other policy objectives, by and large, draws on the right policy instruments. A more systematic measurement is needed of the trade spillovers from these instruments, and their coherence across policy areas. Internationally, the UK’s main challenges reflect the fact that its trade costs with its two major trade partners – the EU and the US - have risen, in a context of fragmenting global trade. Moreover, the US pursuit of a WTO-minus approach, and pressures on partners to adhere to this approach, presents the UK with particularly pointed trade-offs, given its interest in and commitment to multilateral arrangements.

These observations also point to certain institutional steps that the UK could take to manage the complex trade-offs that arise in the conduct of modern trade policy, including those trade-offs that come from the role that trade policies are expected to play in relation to a number of different policy themes. These steps include:

- Open consultation, and better evidence to guide decisions.

- A coordinated, cross-government approach to monitoring and evaluation of trade policies that would help policymakers understand the trade-offs involved and incorporate perspectives on sustainability, inclusion, and regional impact.

- Clarifying how economic security fits within the UK’s avowed commitments to openness and multilateralism, to ensure emerging security-driven arrangements do not undermine global rules and take into account impacts on developing countries.

Recommendations

The report sets out detailed recommendations in each of its chapters, which the reader is invited to examine. Many of these are specific to the particular thematic areas of the study: economic security, trade and digital, sustainability, and inclusion. We present here a non-exhaustive list of cross-cutting recommendations, that can broadly be classified under the following clusters.

Coherence

- Across government and across policy areas: There are multiple policy instruments for specific policy areas – be this digital, climate change, sustainability or inclusiveness. These are often in the hands of different departments or even different units within departments. There is a need for ongoing assessment to ensure the coherence and consistency of policy with regard to each objective and across government departments.

- Across agreements: The Government should undertake an assessment of the overall coherence of the UK’s FTAs and other trade agreements (mini-deals) with a clear focus on the objectives, on the consistency between the provisions on common policy areas across the agreements, and on the effectiveness of those provisions.

- Between domestic and international policy: For greater effectiveness of policy, there should be greater connection between the UK’s multilateral engagement in trade policy, and policy in and for the UK. Examples of this include policy towards sustainability and fossil fuels, or policy with regard to trade and gender.

Institutional strengthening

- Improve scrutiny by parliament of trade agreements. More generally, trade agreements, including ‘non-binding legal instruments’ (mini deals), should be made more transparent with regard to what is being negotiated, with whom, by whom, and with what purpose and legal effect.

- Westminster should build on progress in engagement with the Devolved Administrations through the Intergovernmental Relations Review and consider a formal role for Devolved Administrations in UK trade policy. Without a constitutional basis, inclusion remains based on goodwill rather than legal precedent.

- There should be greater consideration given to overall trade strategy, trade priorities and the effectiveness of trade policy than is currently the case. In so doing, it is important to include the voices and needs of the business community, other stakeholders and experts. These can also raise private sector and broader societal concerns, for example, with regard to inclusiveness or sustainability. To achieve this, we recommend restructuring the Board of Trade as a non-departmental independent public body working alongside government and stakeholders.

- The UK Government should publish an annual report on UK trade policy, with an assessment of UK trade performance and UK trade agreements (including their utilisation and performance), as well as an assessment of the trade barriers faced by UK firms. Such a report could be the responsibility of a reformed Board of Trade. This would provide a summary of what has been achieved, as well as identifying ongoing challenges. Reports could include ex post assessment of policies, their efficacy, and the extent to which the objectives have been realised.

- Consultative processes could be enhanced, both through more systematic consultations with businesses on trade policy measures, in the negotiation of agreements and in their operation and discussions of amendments and further provisions and by ensuring effective participation of stakeholders beyond businesses. This would contribute to more informed and more inclusive policy making.

- An evaluation of public preferences and values attached to international trade and integration is desirable. Understanding and taking on board public attitudes to trade matters for the legitimacy of policymaking and to enable policymakers to assess the trade-offs and the priorities.

International positioning

- While the rules-based multilateral trading system is currently under considerable strain, its fundamental principles of non-discrimination, reciprocity, and transparency remain fundamental to growth, prosperity, and fairness. The UK should continue its positive initiatives on possible reforms of the multilateral trading system. As a long-time advocate of the rules-based system, and an economically significant trading country, the UK has the potential to be an important convenor and facilitator of such discussions, a role it played historically, including when it was an EU Member State.

- The UK needs to balance pursuing its domestic public policy interests with regard to growth, economic security, sustainability and inclusiveness, while playing by the 'rules of the game'. For the reasons outlined above, this should involve adhering to the multilateral rules-based system. Where the Government has stated that it reserves the right to deviate from WTO rules, it should be clear on how it plans to reconcile this with its professed commitment to the rules and how it intends to assess the balance of risks and benefits and trade-offs of these competing positions.

- Given the prominence of economic security as a theme, the UK would benefit from having a policy statement on the matter. This would include a discussion of the principles and routes to intervention on grounds of economic security, how it will respond to pressure and economic coercion from its trade partners, and how it would consult on the need for further legislation.

- The UK needs to work closely with ‘like-minded’ middle-power countries to help steer a cooperative path which respects the principles of the rules-based international trading system. This should include continuing to pursue free trade agreements with partner countries, in part as a means for further trade liberalisation, and in part to allow for the inclusion of issues which go beyond economic growth and market access but impact sustainability, inclusiveness and possibly economic security. Given the role played by the EU in UK trade, reducing the trade costs imposed by the UK’s exit from the EU is an important priority.

Support for businesses

- In support of the government’s growth objectives, there is a need for practical and coordinated policy (e.g. advice, finance, taxation policy, trusted advisor, business mobility, trade diplomacy) to support business, especially SME’s, having access to imports, entering export markets and expanding sales.

- Collaboration on matters of regulation and broader policy objectives with partners that differ widely in their institutional arrangements presents complex challenges. The UK should aim for mutual recognition agreements in order to reduce technical barriers to trade by decreasing the need for products to be retested, inspected or certified for export markets.

- There should be greater recognition in trade policymaking of the importance of services trade and the linkages and synergies between services and goods trade, and thus on services and goods trade policy. As a services economy, UK trade policy should address services trade barriers and consider whether more could be achieved both in FTA negotiations with sector-specific commitments, as well as through agreements between regulators, memoranda of understanding, sector-specific behind-the-border unblocking of specific issues, and business mobility.

- Business is more vulnerable to the actions of state backed actors, transnational crime, natural disasters, and geopolitical tensions than ever before, and is increasingly subject to supply chain regulatory requirements. This requires more communication, information exchange and closer partnerships between the state and the private sector. It also leads to a greater need for governments to help businesses (especially SMEs) with regard to regulatory compliance, managing risk and considering when the Government may need to underwrite risk.

- Policy needs to recognise that there are both winners and losers from changes in trade and trade policy, and differential impacts on firms, workers, consumers and regions. An inclusive trade policy requires effective adjustment and mitigation levers for those negatively impacted. In part, this is important to ease the social costs, in part this is to facilitate adjustment and transition and in so doing contributing to higher long-run rates of growth.

Introduction

Why undertake an independent review of trade policy?

Making trade policy is difficult and, in today’s world, arguably more challenging than ever. This is due to a confluence of factors, including long-standing concerns about environmental issues, equity and human rights, and more recently concerns reflecting the interplay of technological change, geopolitics and economic security. Trade policy has also had to contend with the effects of global events, such as pandemics, migration, and wars. Increasingly, there are also concerns about the ability of the rules-based world trading system to deal with these challenges, especially with regard to economic security.

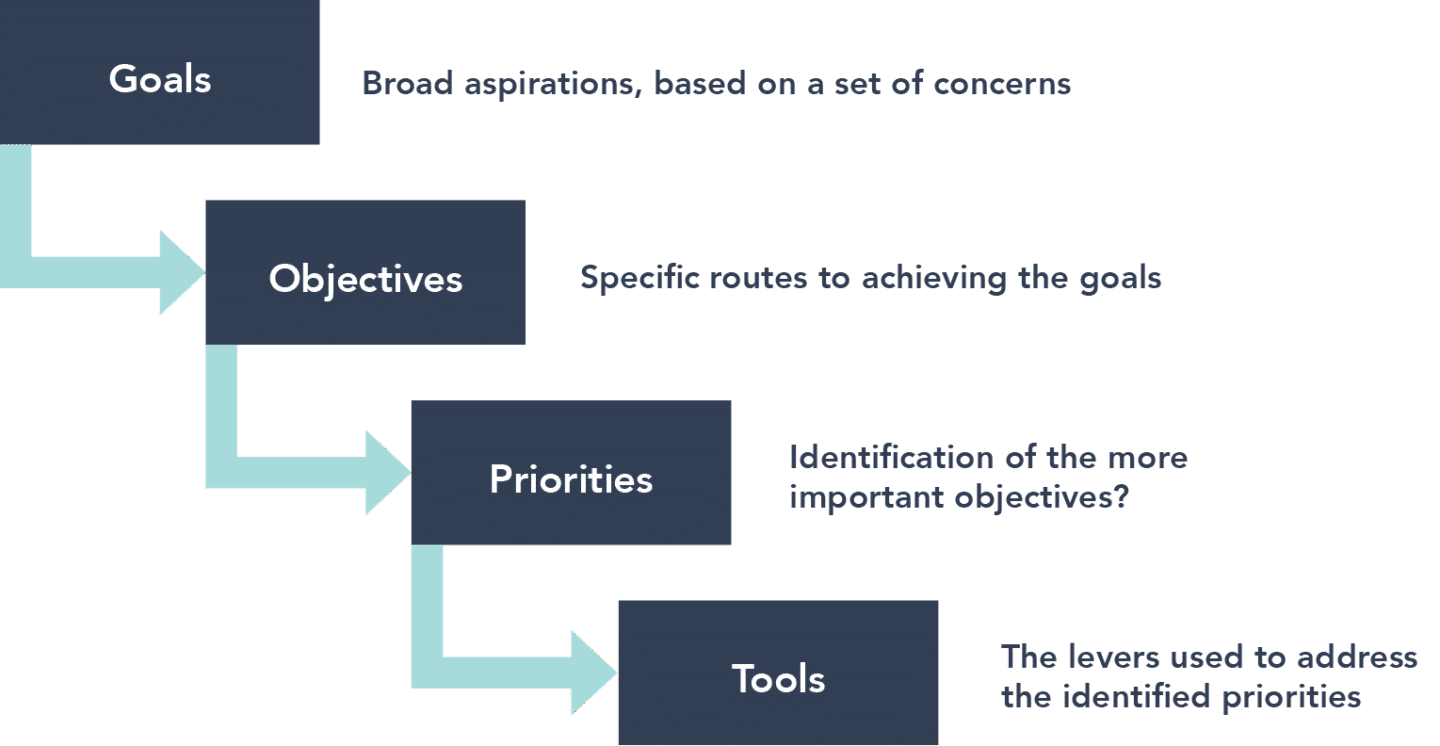

In this context, this report provides a comprehensive review of the UK’s trade policy and the extent to which it addresses today’s challenges. This involves understanding the key features of the UK economy and the international context in which it operates, identifying the objectives and priorities of UK trade policy, the policy instruments used and policy decision-making processes, and how they aim to contribute to broader public policy goals. The timing of this report coincides with the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) review of the UK under the auspices of the Trade Policy Review Mechanism (TPRM).

The WTO review is the first of the UK since the UK reacquired competence over its trade policy following its exit from the European Union. The WTO TPRM was established in 1989, during the Uruguay Round trade negotiations, and was intended to enhance transparency and understanding of global trade policy.1

The formal WTO process takes the form of a periodic review. It is based on reports published by the WTO secretariat, and by the authorities of the country under review. These reports are then discussed at meetings of the WTO’s Trade Policy Review Body (TPRB), with WTO Members having the opportunity to put questions in writing to the member under review.2 In the case of the UK the TPRB meetings took place on 28 and 30 October 2025. This formal process was never intended to be an end in and of itself, but rather to be a starting point for an ongoing dialogue on the functioning of trade policy.3 It is to that ongoing process which this report intends to contribute.

It is worth noting that trade policy is a broad term. It is customary to distinguish between direct trade policy instruments and other policy instruments that may not be directly aimed at trade per se but are likely to have trade effects that can be substantial. A trade policy instrument is a tool whose primary intention is to impact or regulate international trade in either goods or services and thus modify or influence trade flows between countries. Examples include tariffs, export subsidies and controls, or limits on the number of foreign service providers. These instruments impact either the ability of other countries to access your market or your ability to access their market. Other policy instruments, such as innovation policy, domestic regulation, taxes on environmental externalities (such as carbon pricing), or industrial subsidies, have as their primary goal non-trade objectives but are likely to materially impact trade. The distinction is implicit in the structure of trade rules: these are comparatively more stringent in relation to the ”direct” trade policy instruments, and more permissive in regard to other instruments, in relation to which the focus of rules is to mitigate the extent of trade policy spillovers.

In practice, the two types of policy instruments are closely related as changes in trade policy will also impact non-trade objectives, and changes to other policy instruments will impact trade. Indeed, the role of these other policy instruments has become progressively more important. This is partly because tariffs have fallen globally (recent events notwithstanding), and because of the growing role of services trade. The primary trade measures affecting services are really about the contestability of domestic markets, and regulatory issues are particularly important in services. The interaction between “trade” and “other” policy instruments has been further reinforced by the pursuit of multiple policy objectives, such as environmental goals and economic security, that have domestic and global dimensions with significant trade policy interactions.

In assessing any country’s trade policy, and in the ensuing chapters, it is therefore important to evaluate both types of instruments, while also recognising their specific roles. Key questions in this regard are whether the correct policy instruments have been assigned to the designated policy objective, and the degree of policy consistency and coherence. Such an assessment necessarily requires a thematic approach, i.e. one that identifies specific policy topics that are a priority to governments, and that provide the context for trade policy, in particular, the use of instruments that have trade policy spillovers. This report takes such a thematic approach with chapters on economic security, digital trade, sustainability and inclusiveness, a selection that is based on a textual analysis of UK Government policy priorities within the evolving global context for trade policy (see below).

The thematic approach is the principal point of differentiation between this report and the WTO process, and specifically the WTO Secretariat’s report. In following this thematic approach, we aim to support the overall objective of transparency that lies at the heart of the TPRM. Moreover, by following a thematic approach, and by exploiting new analytical methodologies, the report seeks to model how modern trade policy reviews can be done. This is particularly the case given the complex challenges facing trade policy in the current global context.

The evolving global context for trade policy

It is useful to place the current challenges in a historical context. Trade policy has always been about economic benefits mixed with addressing foreign policy concerns, while also responding to domestic political economy pressures. For centuries and up to the mid-19th century, the approach to trade in most countries was largely mercantilist. This meant that the objectives of trade policy focused on maximising exports relative to imports, protecting domestic industries from foreign competition and encouraging infant industries. An additional objective was revenue generation. This approach was prevalent especially during the early 19th century, as countries — notably in the US and Europe — sought to build their industrial bases.4 From the mid-19th century onwards, there was a shift to more liberal trade regimes with reductions in tariffs, as seen in the repeal of the Corn Laws in the UK, and the signing of trade agreements such as the Cobden-Chevalier treaty between Great Britain and France in 1860.

Following the First World War, many countries were faced with reconstruction, the demobilisation of millions of soldiers and integrating them into the workforce, the pressure of war debts, (hyper)inflation and considerable instability. Especially with the onset of the Great Depression, which began in 1929, this led to a rise in nationalism and economic pressure to protect domestic industries with tariffs as a perceived necessary defensive measure. This was exemplified by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 in the US, which raised tariffs to record levels, and in turn, led to a cycle of retaliation by other countries and a collapse in world trade. At the same time and partly in response, Britain also sought to encourage and liberalise trade within its empire with the 1932 Ottawa Agreements.

The post-World War II period saw a substantive shift towards trade liberalisation and economic cooperation based on principles of non-discrimination. In particular, the principle of Most Favoured Nation (MFN) treatment was strongly advocated by the US, which had formed the view that the system of imperial preferences and bloc rivalry between powers was one of the driving forces behind the conflict. After a certain degree of resistance, by the UK in particular, MFN was adopted, along with National Treatment, as the foundational principles of trade via the establishment of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947. Under the GATT, eight “rounds” of trade negotiations were held, the last of which was the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations (1986-1994), and which led to the creation of the WTO in 1995. Tariff levels fell from roughly 22% on average in 1947 to around 5% after the Uruguay Round. The creation of the WTO also included the extension of trade rules to services and intellectual property, reflecting reforms undertaken by countries globally. Trade policy reforms and rule-making led to a dramatic rise in trade and economic growth.

The key principles of that post-World War II approach were the multilateral liberalisation of barriers to trade, non-discrimination, reciprocity and transparency all within a rules-based system. Those rules aimed to ensure predictability, fairness, stability, and dispute settlement.

This post-World War II approach to trade policy was premised on the recognition that trade openness and multilateral trade liberalisation — based on the preceding principles — would lead to higher rates of economic growth and thus improved living standards. Trade related drivers of growth are typically thought to be innovation, competition, the diffusion of knowledge and spillover effects, gains from economies of scale and the gains from specialisation, underpinned by investment.

This approach to trade policy led to decades of global economic integration driven by the lowering of policy barriers to international trade in goods and services, as well as investment, and to a lesser degree, the mobility of people, as well as reductions in transport and communication costs across countries. This is often referred to as “globalisation”. The term may be overused, but at its heart was the geographic unbundling of different parts of the production process, enabling production of those parts to take place in different locations / countries, and as businesses sought greater efficiencies through specialisation and scale. The unbundling was driven by and favoured the diffusion of knowledge and innovation all contributing to economic growth.

At the same time, the process of globalisation led to distributional consequences – winners and losers. The most direct and visible winners were consumers, who benefitted from a greater variety of goods at lower prices, which translated into increased purchasing power for households. On the production side, the winners were primarily firms and workers in export-oriented sectors. Many firms that import intermediate goods and raw materials also benefitted from lower costs, helping to increase their competitiveness and profitability.

However, not all firms and industries gain as there is also contraction and market exit by firms. The most significant negative impacts were felt by workers and firms in import-competing industries, which are the most directly exposed to competition from cheaper foreign goods. Such negative effects are often highly concentrated, impacting specific regions or towns that may be heavily reliant on a single industry, such as manufacturing. Indeed, typically the benefits —lower prices and greater choice — are usually widely dispersed across consumers. In contrast, the losses — job cuts and factory closures — are typically more concentrated and therefore more deeply felt by a smaller group of workers and their communities. Hence, from a political economy perspective, the losses are felt more acutely and the "losers" have a much stronger incentive to organise and lobby against trade liberalisation. The negative effects of trade may also fall disproportionately on less-skilled workers and on regions with a high concentration of traditional, import-sensitive industries, which can exacerbate existing inequalities and be of long duration.

The post-World War II approach was also predicated on a belief, and by and large consensus, that closer economic integration as well as delivering higher rates of economic growth, would result in greater interdependence between economies, which in turn would be a force for greater international political stability.

Contemporary challenges for trade policy

That consensus and the rules-based system are now under strain due to several interconnected factors, which are listed below. These are purposely not listed in any order of importance, as views on which are more significant vary, but most of what is listed below appears in current discussions:

- Low rates of economic growth. This impacts on standards of living and public perceptions of domestic and international policy, and raises concerns regarding the distributional effects of economic integration.

- Unforeseen ‘events’ which materially impact on people’s lives and livelihoods. For example, Covid-19 or extreme weather events, which have highlighted concerns about the resilience of supply chains and economic security.

- The political or economic actions of other nation states. These are wide-ranging, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the tariffs and related policies introduced by the current US administration, or the various export restrictions introduced by China.

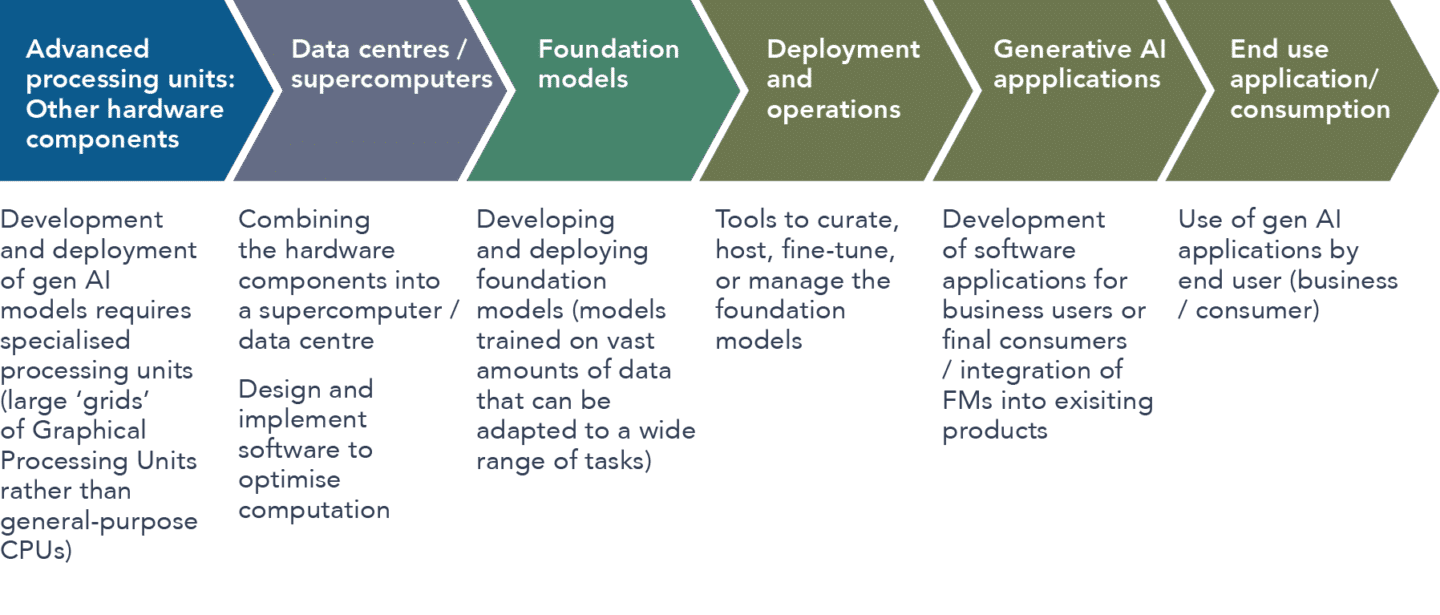

- Rapid changes in technology and digitalisation. This has consequences for jobs and competitiveness, and impacts what is traded and how it is traded. The emergence of digital technologies marked by high degrees of concentration and market power has also created more scope for policy interventions, whether in the form of industrial policy to develop “home-grown” capability to reduce reliance on foreign suppliers, and / or regulatory measures to deal with the possible economic and public policy effects of dominance.

- Climate change, and heightened public and policy concerns about global warming, the environment and biodiversity.

- Heightened public perceptions about the benefits of globalisation, the impact on workers, concerns about the cost of living and thus what people want from trade policy.

As a result of these factors international trade policy is currently being made in a climate of low growth, increased polarisation within countries, increased geopolitical tensions (notably between the US and China) decreased trust between countries, increased policy interventionism (ranging from industrial policy to the introduction of trade barriers which explicitly discriminate between countries), and the decreased belief by policy makers in the ability of the private sector to manage risk. Interdependence, which was believed would lead to greater international stability, is being increasingly weaponised such that in the eyes of some, interdependence is no longer a strength of the system but a weakness.

This has led not only to changes in approaches to trade policy per se but has also seen the rise of industrial policy. As with trade policy, the primary motivation for industrial policy is typically economic growth. Industrial policy, however, is explicitly concerned with domestic policy concerns – be they to do with growth, the distribution of economic activity, or domestically-focused policy interventions ranging from investment, innovation or the regulatory framework.

As a result of all the preceding, while the growth-enhancing effects of trade continue to be seen as a central trade policy goal, other factors now come into play more strongly than was previously the case.

The factors concern:

- Equity: This includes issues ranging from jobs, labour rights, regional development, Small and Medium Size Enterprises (SMEs), gender, and impacts on developing economies.

- Sustainability: Primarily concerning climate change, biodiversity and the environment.

- Economic security: This is difficult to clearly define but is essentially concerned with a country's ability to protect its economy from internal and external threats like supply chain disruptions in critical sectors, economic coercion, and cyberattacks, and to maintain its growth and stability.

The principles of multilateralism, trade liberalisation, non-discrimination, reciprocity and transparency, and adherence to a rules-based system outlined earlier are all being challenged by one or more of the above factors.

Structure and organisation of this report

UK trade policy is being shaped within this complex context. This underscores our opening observation that trade policy is challenging and reinforces the view that assessing trade policy needs to go beyond primarily focusing on a cataloguing of measures. For these reasons, this report takes a thematic approach which assesses the ways in which policy is responding to these broader challenges.

The report draws on a range of information and data sources to detail the key relevant elements of the UK’s trade policy. These include:

- Data provided by UK authorities and international organisations, and our analysis of these;

- Government publications and statements, from 2019 onwards, including the recently published Industrial Strategy and Trade Strategy;

- The (trade) agreements the UK Government has signed with other countries (which may or may not be legally binding);

- The authors’ expert knowledge as well as that of other trade specialists, and various forms of consultation, including a call for evidence, roundtables, and a Citizens’ Jury, which helped us understand people’s priorities with regard to trade and trade related issues.

The report consists of eight chapters:

Chapter 1: We present an overview of UK trade and economic performance. This provides important context as to what the UK trades, with whom, and how, and how this has evolved over time.

Chapter 2: This is primarily based on a detailed examination of a range of government documents which we refer to as the ‘trade corpus’. The aim is both to understand UK trade policy and provide a systematic and robust methodology applicable in future years, or by other countries, or other policy contexts.

Chapter 3: Details the main domestic processes and legislative frameworks through which the key elements of UK trade policy are made. We also discuss the more informal consultative arrangements in place through advisory groups, as well as the role of the UK Devolved Administrations in the making of UK trade policy. The chapter also discusses the UK trade remedies regime, the subsidy regime, and business support policies.

Chapter 4: Examines the aspects of trade policy that are based on international agreements or coordination with other countries. We consider the UK’s role and position in the WTO. This includes Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) conforming to WTO rules and what may be more loosely described as mini deals, as well as policy towards developing countries with discussion of the UK Developing Country Trading Scheme (DCTS) and its Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs).

Chapter 5: This identifies the different ways in which economic security has become an important focus of trade policy. It highlights the wide range of objectives that come under the umbrella of economic security, the possible trade-offs that exist between these objectives in and of themselves, and in relation to economic growth. It then examines how economic security is addressed in the UK through its policy positioning and legal frameworks, and how economic security questions are addressed in trade agreements.

Chapter 6: Explores the complex relationship between the digital transformation and international trade. We focus on how trade has influenced digitalisation, and on how digitalisation, by reshaping trade and economic activity, can contribute to productivity and economic growth. We examine the dimensions of digital and trade interaction and provide a background to the UK’s digital trade trends and comparative advantage. We then explore the policy and regulatory settings that impact digital trade in the UK and the trade policy measures and arrangements internationally, including FTAs, digital agreements and other forms of cooperation as well as through the WTO.

Chapter 7: Reviews the relationship between trade and sustainability in UK trade policy. It highlights the UK Government’s core goals and objectives relating to trade and sustainability, and the relevant trade policy instruments proposed and adopted; what trade-offs between sustainability and trade are addressed in UK trade policy; and how the Government’s core goals, objectives and trade policy instruments align with business and UK consumers’ priorities.

Chapter 8: In this chapter, we examine how trade policy impacts two dimensions of inclusivity: employment and gender outcomes in the UK. We recognise that these are also closely related to other dimensions of inclusivity — such as impact on small and medium-sized enterprises and regional disparities — but those topics fall outside the scope of this report. We first consider the overall framing of trade and labour market outcomes, and trade and gender outcomes respectively, then move on to a discussion of their inclusion and treatment in UK FTAs.

Finally, it is perhaps worth noting what this report does not do. First, there are inevitably areas of policy which we have not covered – either because we considered them out of scope, or because we had to draw the line somewhere. The list of these might include the causes of week productivity performance, challenges and options for WTO reform, detailed analysis of the Industrial Strategy and sector plans, an in-depth discussion of broader regulatory and digital policy settings, a comprehensive review of the landscape of UK domestic policy with regard to sustainability and the impacts on trade and trade policy on SMEs or on regions.

Second, this report is not intended as a forward-looking “trade strategy”. The focus is on detailing and understanding UK trade policy priorities, and on the basis of those priorities assessing the policy framework. Assessing policy inevitably leads to recommendations as to what else could be done, or what could be done ‘better’. Hence, at the end of each of chapters 3-8 we provide a set of recommendations based on our analysis and on our consultations. The spirit behind our report and recommendations is that we aim to provide an informed critique of UK trade policy, and not a criticism. Indeed, there is much to be welcomed with regard to UK trade policy and its articulation in a trade strategy, and this report should be read in this light.

References

Chapter 1 UK trade and economic performance

Chapter overview

This chapter provides an empirical backdrop to the remainder of this report based on descriptive statistics on the UK's economic performance, on UK trade patterns, and how they have evolved over time. We also provide information on the number of UK jobs associated with UK trade, as well as looking at investment flows.

Key points

- UK productivity and GDP growth have lagged behind comparator countries over the last decade or more.

- The UK is a relatively open economy, with the sum of exports and imports of goods and services relative to GDP of around 65%. This underscores the importance of international trade to the UK economy.

- The UK is predominantly a service economy, with a services share of 54% and 34% in total exports and imports respectively. In 2024, 70% of those services exports were digitally delivered.

- The UK’s top exports and import partners in 2023 were the EU, the US and China, accounting for 41%, 22% and 4% of UK exports of goods and services; and 52%, 13% and 7% of UK imports of goods and services, respectively.

- Out of all UK firms, a relatively small share are directly involved in either exporting (11.5%) or importing (12%), and only 6.5% of firms both export and import.

- Only just over 60% of UK exports and less than 40% of imports are undertaken directly by firms classified as producers, the remainder is undertaken by distributors or by firms classified as service providers.

- Trade is important for UK jobs, with over 30% of UK employment directly associated with firms that export. Excluding agriculture, finance and public administration, and defence this accounts for more than 6.5 million employees.

- Of the 6.5 million export jobs, just under 5 million were in services, and just over 1.5 million were in goods / manufacturing. In turn, this highlights the significance of services exports for the UK economy.

- Since 2015, employment growth in the UK has occurred primarily among non-exporting as opposed to exporting firms, and primarily in services sectors as opposed to manufacturing. Manufacturing firms that export have seen a decline in employment, and particularly male lower-skilled employment.

- On average, the share of foreign intermediate inputs used in UK exports is just under 16% in total, and 28% for manufacturing, and 43% of this is from the EU. This reflects the UK’s close integration in global value chains, especially those of the EU.

- Over the last decade, there has been a significant rise in the closer interlinking of goods and services exports in two dimensions: the use of imported services as inputs for final exports, and the bundled exporting of services with goods by firms.

- Data on inward FDI into the UK suggests that investment, of which services are the most important element, has barely recovered following a substantial dip in 2020. In contrast, UK outward FDI, again primarily in services and within that business services, has risen and to a comparable degree as the US and the EU.

- Empirical evidence suggests that leaving the EU has impacted negatively on UK exports and imports of both goods and services, relative to what would have been otherwise the case. The estimates vary, with upper-bound estimates suggesting that the impact could be as high as a decline of 30% for UK trade in goods (both exports and imports) with the EU and a decline in exports of 16% for those services sectors with larger rises in trade barriers.

1.1 Trade and economic performance

1.1.1 UK productivity and economic growth

Before looking in more detail at UK trade, we first provide a brief overview of the overall performance of the UK economy. This is important because, as will be seen in Chapter 2, the main objective of UK trade policy is to increase economic growth.

UK economic performance since the financial crisis of 2008 is often described as being characterised by a ‘productivity puzzle’, which essentially refers to comparatively low productivity in the UK, and, closely related, the low growth of UK productivity and thus economic growth over this time period. These graphs shed some light on this. Figure 1.1 gives the gross value added per hour (GVA/hour) worked for the UK and a range of comparator countries for 2023 (which was the latest year for which the data was available). GVA/hour is often used as a proxy measure for labour productivity. In Figure 1.1, it can be seen that UK labour productivity is roughly 25% lower than in the US, and 10% lower than in Germany and slightly lower than that of France, but it is higher than the European Union (EU) average or the other countries in the figure.

Source: OECD productivity database

If we consider changes over time, Figure 1.2 tracks UK GVA/hour worked for the same group of countries, and in each case relative to 2015. What is noticeable is that UK labour productivity growth was lower than all the countries other than France from 2015 onwards, and unlike most of the other countries has stagnated since 2020.

Source: OECD productivity database

The next figure, Figure 1.3, shows the change in UK GDP (Gross Domestic Product) (volume index) relative to 2015, for the UK and for all the OECD countries, as well as the OECD aggregate.1 From this, it can be readily seen that UK GDP growth was towards the bottom of the OECD group of countries, and there was a sharper contraction in 2020 for the UK in comparison to the OECD and most other countries, followed by a recovery, which again was lower than the OECD average.

Source: OECD Quarterly GDP and components – expenditure approach – volume and price indices

It is not within the scope of this report to discuss the causes of this relative performance and UK productivity puzzle in detail, but it is worth highlighting some of the key factors which the literature has identified as explaining this low productivity growth. Those factors include: a lack of investment, both public and private, in capital and skills; the poor diffusion of technology, innovation, and productivity-enhancing practices both across firms and between different regions of the UK; the lack of coherence in policy across institutions; the quality of UK infrastructure; and poor quality of management.2

This poor comparative performance of the UK economy also helps to explain why the focus of UK policymaking by both the current and preceding governments is on economic growth. The factors driving that poor performance provide an indication of the constraints and issues that policy (and in the context of this report, trade policy) needs to address to improve UK economic performance.

1.2 The role of trade in the UK economy

1.2.1 Openness to trade

We now turn to considering the relative importance of international trade both in goods and services for the UK and some comparator countries. This is typically given by a measure of openness, which takes the ratio of total trade in goods and services to total GDP. This is given in Figure 1.4.

There are several features worth pointing out. First, the UK’s openness to trade (measured by the ratio of imports and exports to GDP) is currently around 65% which highlights the importance of trade for the UK economy, and thus the potentially significant impact that changes in trade can have both on overall economic activity in the UK, but also on the distribution of that activity.

Second, there is a wide variation in openness across countries. The UK’s level of openness is thus roughly the same as the average for the OECD but lower than that of the EU as a whole (which is close to 100%), and higher than that of the United States (US) (which is just over 20%). It is important to note that levels of openness do not necessarily reflect whether or not a country is more or less protectionist. The United States (US), for example, typically has a low level of openness because its size means that it is able to supply many more goods domestically and thus is less reliant on trade.

Third, if we look at changes over time, we see that for the OECD as a whole, openness has risen from 26% to 58% over the time period, and for the UK from 43% to 64% while also fluctuating more. For the last decade or so, UK openness has changed very little, though there was a decline in 2023. This compares markedly to the EU, which has seen a rise in openness since 2023 from 84% to 95%. Finally, it is worth remarking on the decline in the openness of the Chinese economy from above 60% to below 40% since 2004.

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators

The importance of international trade for the UK is not only reflected in the share of trade in UK GDP and in the value of UK exports and imports, but also in the number of enterprises involved in UK trade, the types of firms that engage in trade, and the numbers of workers engaged in trade either directly or indirectly. Each of these is discussed in the following subsections.

1.2.2 UK firms and trade

Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates indicate that in 2023 (the latest year for which data is available), out of a total number of UK enterprises of just over 2.4 million, there were nearly 280,000 firms exporting and over 290,000 firms importing.3 The shares of the firms that engage in either exports and imports in total and separately for goods and services is given in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Share of Firms that Trade (2023)

| % of firms that are: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exporters | Importers | Both Exporter and Importer | Either Exporter or Importer | |

| Total | 11.5 | 12.1 | 6.5 | 17.0 |

| Goods | 4.1 | 6.7 | 2.6 | 8.2 |

| Services | 8.4 | 7.0 | 4.1 | 11.3 |

Source: Own calculations from the ONS, Annual Business Survey exporters and importers, June 2025

The first row of the table indicates that, in total, 11.5% of UK firms export, 12.1% import, 6.5% of firms both export and import, and 17% of firms either export or import. An important feature of this data is that the overwhelming majority of firms that engage in trade are small firms (defined as those with between 1 and 49 employees). Out of all the firms that either export or import goods or services, 95% of these were small firms. However, the overall importance of trade for small firms is lower: Out of all small firms the share that engaged in international trade was only just over 16%. This means that 84% of small firms do not directly engage in importing or exporting. Conversely, if we consider large firms (those with more than 250 employees), more than 55% of these firms engage in international trade.

1.2.3 Producers, distributors and services firms in UK trade

Figure 1.5 and Figure 1.6 consider another characteristic of UK trade. We focus only on trade in goods, and examine, over time, the extent to which that trade is undertaken by producers, distributors or services firms.4

Source: Own calculations using ONS-HMRC TiG-IDBR dataset

Source: Own calculations using ONS-HMRC TiG-IDBR dataset

There are at least two interesting features which emerge from this data. First, it can be seen that just over 60% of UK exports and less than 40% of UK imports are undertaken directly by firms who consider themselves producers. This suggests that a high share of UK goods exports is either undertaken by distributors (as opposed to by the producers themselves), or by firms which are classified as services firms. Each of these latter categories account for around 20% of UK exports. Similarly, when it comes to imports of goods just over 50% is carried out by firms classified as distributors.

From a trade policy perspective, the composition of firms engaged in trade is important, especially when broken down at a more detailed sectoral level. For example, the data indicates that in 2020, 76% of UK exports of textiles and clothing were undertaken by distributors. By 2022 this had declined to 63%. A good part of this decline in the share (and value of exports by distributors) was driven by a decline in exports to the EU. A plausible explanation for this decline in textile exports by distributors is the difficulty such exports would have had in satisfying the rules of origin requirements for duty-free access to the EU. In comparison, the share of producers in the exports of ‘advanced manufacturing and machinery’ is over 80% and these firms may well have been less affected by the rules of origin requirements, as there was sufficient domestic content to meet the requirement. This indicates that how trade takes place and who does the trading varies considerably across sectors (and no doubt also between firms within a sector), and changes in trade policy will thus have differential impacts.

The second interesting feature concerns changes over time, and in particular, since 2020 hence around the time of the UK’s exit from the EU. With regard to exports, we see a clear decline in the share of exports undertaken by distributers and a modest decline in the share undertaken by producers, with a rise in the share of services firms engaged in exporting goods. On the import side, and conversely, we see a decline in the share of goods imports by services firms and rise by both producers and distributors.

1.2.4 Jobs in trade

As discussed earlier, the share of imports and exports in UK GDP is a little under 65% and this highlights the importance of international trade for the UK economy. This importance is then reflected in the number of jobs that are associated with the trading activities of firms. One important dimension of this concerns the levels of employment, and changes in those levels associated with exporting firms. This is also particularly relevant with regard to the discussion regarding the winners and losers from changes in trade and trade policy. Those changes in trade, which may be policy induced, typically lead both to changes in specialisation across industries according to comparative advantage, and within industry changes depending on the underlying competitiveness of firms. This leads to firms contracting / expanding, new firms entering the market, and some firms closing down, as well as changes within existing firms. In turn, all these changes will impact the levels and composition of employment in the economy. The result may not only be immediate job losses but also gradual erosion of local economies, especially in regions that rely heavily on these sectors.

In this section, we present evidence on those levels and changes in composition, where we draw heavily on a recently produced ‘jobs in trade’ database.5 The data is for the period 2015-2022, and covers a substantial proportion of the UK economy. Notably, however, and because of the nature of the underlying surveys, the database excludes financial services, agriculture and public administration and defence. The sectors covered account for just under 24 million full-time equivalent employees in 2022.6 Of these, nearly 6.5 million employees, which accounts for 31% of the total, worked for exporting firms.7 This figure only takes into account the direct employment associated with exporting and does not take into account indirect employment associated with domestic firms which supply inputs to those firms that export. As we saw earlier, only a small proportion of UK firms (11.5%) directly engage in exporting, but many more will be indirect exporters.

It is important to note that the share of workers associated with exporting activities varies considerably across sectors and industries. Hence, of the 6.5 million export jobs, just under 5 million were in services, and just over 1.5 million were in goods / manufacturing. This underlines a distinctive feature of the UK which is its reliance on services and services exports for the UK economy. Also important is the role of digitally enabled exports in finance, business services, and creative industries. OECD research indicates that around 3.2 million UK jobs were directly embodied in digital services exports in 2019, with median wages in these sectors generally above the national average.8

While there are thus many more jobs associated with services exports than manufacturing exports, the relative importance of exporting versus non-exporting jobs is considerably lower in the service sector. This can be seen in Figure 1.7 which gives the shares of employment across exporting and non-exporting firms for manufacturing and services sectors. From this, we see that exporting firms account for just over 65% of employment in manufacturing firms, but only 26.2% for services firms.

Source: Jobs in Trade Database

The changes in employment levels over time are also revealing, and these are given in Figure 1.8, which depicts the change in employment in both manufacturing and services over the period 2015-2022. There are two key messages which emerge from this figure. First, we see that overall employment in the UK has risen over this seven-year period, by nearly 740,000 full-time employment jobs. Second, the increase in employment is driven by changes in services as opposed to manufacturing. Indeed, employment in manufacturing has declined overall (by nearly 50,000), and in turn, this is driven by a decline in employment in exporting firms.

We do not have a clear picture as the causal factors driving all these changes, however, related ongoing research undertaken by the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) suggests that UK firms more exposed to trade with the EU reduced their employment levels following the 2016 referendum; and that by 2022 exporters had reduced employment by 13% and importers by 10%.9

The changes in employment levels are also likely to have been affected by changes in migration flows following the Brexit referendum, where the UK experienced a reduction in inflows from the EU and particularly with regard to low-education / low-skilled workers. There is not space in this report to discuss migration and its impacts, but it is also worth highlighting that changing patterns of migrant workforce composition are also likely to impact firm-level performance. Empirical evidence suggests that migration brings differences in skills, and can also lead to improved firm-level productivity.10

Source: Jobs in Trade Database

There are two other dimensions with regard to the relationship between trade (exporting) and employment and these concern gender and skill levels.

Studies on gender segregation in the UK labour market show that women remain concentrated in female-dominated sectors with weaker contractual protections and lower average pay.11 Research further highlights that job mobility typically delivers smaller earnings returns for women compared to men, suggesting that women may not benefit equally from the reallocation effects triggered by trade liberalisation12. For businesses, this matters because a narrowing of labour opportunities for women undermines the goal of harnessing the full talent pool while for policymakers, it raises questions about whether trade agreements or strategies are sufficiently “gender-sensitive.”

If we consider the gender dimension in the jobs in trade dataset, we see that while the share of female workers across all the sectors is 46%, the share in exporting firms is 35%. Hence, overall, exporting firms proportionately tend to employ more male workers. This is particularly pronounced in the manufacturing sector where the share of male workers in exporting firms is 78%, and conversely, the share in the services sector is 61%. Gender composition varies considerably across industries. In manufacturing, the highest share of female workers is in textiles clothing and leather (42%), and in the manufacture of food products (35%), whereas it is considerably lower in machinery (15%) and in vehicles and transport (15%). The work cited earlier by the OECD suggests that digitally-delivered service exports appear to exhibit higher female participation compared to traditional exporting industries. A possible explanation for this concerns the ways in which digitalisation facilitates trade through lowering distance barriers, lowering entry barriers, and allowing for more flexible forms of working.

The changes in employment by gender in the UK are also interesting. From the discussion above, most of UK employment growth over 2015-2022 was within the services sector, and within non-exporting firms. The increase in employment was also very evenly distributed between male and female workers, and consequently the share of female workers in services over the period 2015-2022 has remained fairly constant over time. In contrast, for manufacturing, the loss of jobs depicted in Figure 1.8 is almost entirely driven by a decline in male workers in exporting firms, resulting in a small decline in their share. Whilst there has been a modest increase in female workers in manufacturing, this is almost entirely driven by an increase in non-exporting as opposed to exporting firms.

Turning to the skill dimension, we consider the distribution of low and high-skilled employment between exporting and non-exporting firms, and consider any differences between manufacturing and services.13 Overall, the share of low-skilled jobs in 2022 in both manufacturing and services is just under 40%. Note, however, that although the averages are similar there is considerably more variation across the industries within each of these sectors. Hence, in services there are some sectors with a very high share of low-skilled workers such as transport (where the share of low-skilled workers is just under 75%), retail (71%), or accommodation (69%) and others with a much lower share, such as research and development (R&D) (6%), publishing activities (9%) or architecture and engineering (10%). The variation across the manufacturing sectors is not so great.

In both sectors, there has been a movement towards more higher-skilled jobs relative to lower-skilled jobs. This can be seen in Figure 1.9 which gives the change in the shares of each of these categories for both manufacturing and services. From this we see a modest shift towards fewer lower-skilled workers in manufacturing for both exporting and non-exporting firms with changes in shares of 1.7 and 2.7, respectively; with a more substantial change in services where the changes in shares were 6.6 and 6.8, respectively.

Source: Jobs in Trade Database

The preceding serves to underline that there is considerable heterogeneity in the importance of trade and notably exporting for jobs across manufacturing and services, and in the industries within these broad categories. We also see that the growth in UK employment since 2015 appears to have been largely driven by non-exporting firms in the services sector, and there is little evidence of dynamic job growth arising from increased exports. With considerable variation in the gender and skill composition of the different industries too, these changes, in part driven by changes in trade, imply highly heterogeneous impacts for workers, and for different categories of workers. Notably, for example, we see a decline in the share of low-skilled jobs

1.3 Direction and composition of UK trade

1.3.1 Direction of trade

At the end of 2023, the UK’s exports of goods and services came to around £861.2 billion and its imports to around £876.3 billion. The UK’s top export markets are depicted in Figure 1.10

Source: ONS pink book

The leading source markets for UK imports are depicted in Figure 1.11.

Source: ONS pink book

The EU-27 countries, taken as a single market for goods and services, still dominate UK trade, both on the export and import side. The presence of Switzerland and Norway as important trade partners in part reflects the importance of proximity for trade relations, but is also reflective of particular facets of UK trade. These include the role of natural resources (Norway), and trade in financial services and precious metals (Switzerland). Despite their small size, Jersey and the Cayman Islands play significant roles as export destinations, mainly reflecting financial services linkages. The US accounts for around 21% of total exports and 13% of total UK imports, making it the largest country partner of the UK. China is the second largest country partner, accounting for 4% of UK exports and just under 7% of imports.

With regard to trade in goods, the 27 European Union Member States (EU-27) is the UK’s dominant trading partner, accounting for just over 40% of both UK exports and imports. When it comes to individual countries, the US is the largest single country export destination (accounting for just under 13% of UK exports in 2024), and the second largest import source (with 11.5% of UK imports), and China is the second largest export destination (9% of UK exports), and the largest country import source (12.4%). Germany is the UK’s third largest country export partner with 7.6% of UK exports, and 9.6% of UK imports.14